For English please scroll down.

Norihiro Haruta - studentul japonez care a vizitat România în 1990

Norihiro Haruta www.facebook.com/norihiro.haruta născut în Japonia în 1968 a ajuns în România în 1990 căutând revoluția din Europa de Est. Tânăr student ne descrie o Românie și un București exotic pentru el, nemaivăzut până atunci. Interesant este că memoriile lui scrise după 27 ani și-au păstrat naivitatea studentului și transmit foarte bine emoțiile trăite în fața unei lumi total diferite de cea de acasă.

Pe lângă prieteniile de scurtă durată Norihiro Haruta s-a întâlnit cu liceanul bucureștean Valentin Diaconu la Horezu în iarna lui 1990 și au rămas prieteni până în zilele noastre. Valentin Diaconu spune: “M-am întâlnit cu Nori în Horezu în vacanța de Crăciun. Mai târziu, el a venit să mă viziteze în București unde l-am găzduit o perioadă la Ozana unde locuiam cu părinții. Ne-am împrietenit și datorită lui am devenit fascinat de fotografie. În 1996, după ce am terminat studiile economice, am ales să devin fotograf freelancer. În toamna anului 2016, am fost în vizită la Nori, în Tokyo, așa cum i-am promis la începutul anilor '90.”

Arhiva primita de la Norihiro Haruta cu Bucureștiul anului 1990 cuprinde peste 500 de fotografii, mă bucur că Valentin Diaconu l-a convins pe Norihiro Haruta să ne trimită atât de multe fotografii. Această arhivă este pusă în valoare cu ajutorul lui Mihai Petre care a fost minunat și a identificat locurile unde au fost făcute fotografiile acum 27 ani. Îți mulțumesc Mihai, ești un iubitor adevărat al Bucureștiului, un foarte bun cunoscător al lui. Îi mulțumesc lui Sabin Prodan pentru descifrarea englezei lui Norihiro Haruta.

1990 Bucureștiul mai urât decât pe vremea lui Ceaușescu

Nu vreau să cred că așa arăta Bucureștiul anului 1990. Este un București atât de urât că nici pe vremea lui Ceaușescu nu era așa. După 27 ani, cred că am uitat partea urâtă a acelor ani. 1990 a fost primul an după revoluție, țara era condusă de comuniștii din linia a doua, am avut trei mineriade dintre care cea din 13 iunie 1990 a lăsat urme mulți ani. FSN-ul a ieșit câștigător la alegeri în frunte cu Ion Iliescu fost comunist de seamă. Brucan a zis că ne trebuie 20 de ani ca sa ne deșteptăm, a fost optimist.

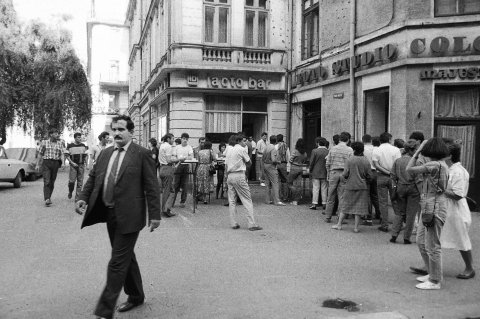

Bucureștiul este groaznic, cu cozi la alimente, oameni îmbrăcați sărăcăcios și urât, înghesuială în autobuze, jucători de alba – neagră și vânzători ambulanți.... un București apocaliptic, degradat, fără speranță, acesta este Bucureștiul după un an de guvernare FSN.

Nori, fotografiile tale, chiar dacă ne plac sau nu, ne dăruiesc o parte din istoria uitată a României foarte importantă pentru înțelegerea acelor vremuri. Ochiul tău nu a iertat, a surprins orașul așa cum era. Îți mulțumesc, îți mulțumesc!

Sper ca aceste fotografii să fie văzute și înțelese de tinerii care au avut norocul să nu trăiască anii comunismului în România.

Andrei Bîrsan, președinte Asociația Bucureștiul meu drag

Interviul lui Norihiro Haruta despre vizita în România

În toamna anului 1989, am fost în China, în zona de interdicție a Tibetului. Am încercat să ajung în provincia Yunnan a Regiunii Autonome Tibet din China, zonă ce nu se poate vizita fără permisiune poliției chineze. În urma unui denunț am fost prins, și interogat în timpul nopții de securitatea chineză, după două zile m-au pus în autobuz cu îndemnul ”Du-te acasă băiat japonez”.

În toamna anului 1989, am fost în China, în zona de interdicție a Tibetului. Am încercat să ajung în provincia Yunnan a Regiunii Autonome Tibet din China, zonă ce nu se poate vizita fără permisiune poliției chineze. În urma unui denunț am fost prins, și interogat în timpul nopții de securitatea chineză, după două zile m-au pus în autobuz cu îndemnul ”Du-te acasă băiat japonez”.

M-am întors la Hong Kong. Hong Kong a fost baza mea, loc sigur și intim de unde puteam să mă întorc la colegiu, la Tokyo, unde studiam Sociologia.

Ca fotograf, știam despre jurnalismul fotografic, despre agenția Magnum și revista Life, dar de fapt nu am știam nimic despre tehnica fotografică. Mi-am cumparat un aparat foto Nikon, filme alb negru Fuji Neopan Presto 400 și Kodak Tri-X 400 și am încercat pur și simplu să fac fotografii. Știu că e tot ce am vrut să fac.

În Hong Kong, am ajuns în noiembrie 1989 unde am văzut știrea despre căderea Zidului Berlinului. Ziare și reviste aveau articole în primele pagini cu fotografii istorice, nemaipomenite. Ar fi fost minunat să pot merge direct la Berlin, din Hong Kong, fără a merge înapoi la Tokyo dar până la urmă am ales să merg acasă.

Din moment ce m-am întors la Tokyo, Europa de Est ținea prima pagină a mass-mediei japoneze. M-am născut în 1968 și am trăit în timpul Războiului Rece dar nu știam prea multe despre comunism și Europa de Est. În fiecare noapte, în cămăruța mea urmăream știrile la televizor despre Europa de Este și mi-am dat seama că reporterii japonezi nu sunt în stare să înțeleagă ce se întâmplă. Televiziunea națională NHK a fost OK compatativ cu celelalte televiziuni.

Între Vest și Est - Asia și Japonia.

Începând cu luna aprilie 1990 mi-am luat liber un an de la facultate și am planificat să vizitez Europa de Est. Am încercat să înțeleg ce este Europa, civilizația europeană modernă și revoluția în Europa de Est.

Ca tehnică foto am avut un Nikon FE, obiective 24 mm, 50 mm, 85 mm, 135 mm și 100 de filme Fuji Presto 400. Nu sunt prea sigur despre aceste lucruri. De fapt, nu-mi prea amintesc ce aparat de fotografiat am avut … a trecut mult timp ...

În perioada iunie – august 1990 m-am dus la Berlin pentru a vedea momentul reunificării dintre Germania de Est și Germania de Vest. Așa a început aventura europeană. Am locuit într-un hostel în Berlin, unde m-am întâlnit cu tineri care au fost în Europa de Est. După Războiul Rece mulți oamenii din Vest au vrut să cunoască Europa de Est, au mers prin Cehoslovacia, Ungaria sau Polonia, dar nimeni în România. Într-o noapte când discutam cu mai mulți excursioniști despre viitorul european economic și politic (nu prea înțeleg bine engleza dar a fost OK), la televizoar se dădeau știri despre România. Mi-a plăcut și am fost interesat, dar ceilalți excursioniști au spus că revoluția s-a terminat în Cehia, Polonia și Ungaria, dar România era încă în procesul unei revoluții, locul unde poliția română bătea studenții în București. Am simțit că acesta este momentul pentru a cunoaște revoluția. Am întrebat ce au mai spus la televizor dar nici unul nu știa limba germană.

După o clipă, m-am hotărât să merg în România ca să simt revoluția.

Și așa am luat trenul de la Berlin la București. În timpul nopții, trenul sa oprit în cele din urmă, la granița dintre Ungaria și România. La miezul nopții, vameșii au intrat în tren și au verificat bagajele și pașapoartele. Erau niște oameni străini care miroseau a alcool și brânză. De fapt, tot trenul mirosea haotic, pentru o persoană care vine din Japonia. Tot corpul meu a reacționat, toate simțurile mele s-au trezit (nasul, corpul, sângele, vocea, erau total diferite).

La scurt timp după răsăritul soarelui, după trecerea frontierei, trenul a intrat în România. M-am uitat pe fereastră și am văzut câmpul de aur, simplu, frumos, cu grâu sau lanuri de porumb. Apoi pasagerii din tren s-au schimbat. Vorba în compartimentul era calmă acum. După drumul lung și agitat de la Berlin, acum era liniștite și blândețe, asta m-a făcut să mă amuze. La miezul nopții trenul a sosit la București, în Gara de Nord. Am găsit un hotel aproape de gară, cu 20 $ pe noapte.

M-am trezit dimineața târziu și recepționiera mi-a spus despre un restaurant din apropiere. Am deschis ușa, am ieșit și am văzut pentru prima dată Bucureștiul în lumina soarelui. Este sfârșitul lunii august cu o vreme minunată. Stăteam în fața acestui oraș. Asta a fost undeva ce n-am mai văzut niciodată. Un oraș plin de praf în soare, tramvaiul care rulează pe strada pietruită, clopotul de apel, căruțe trase de cai ... A fost cu totul diferit de Berlin.

Bucureștenii au fost prietenoși. Mi se spunea"Frate". Uneori am stat în casa cuiva, student, muncitor, prieteni ai prietenilor. Unii oameni au fost incredibil de prietenoși pentru mine și m-am apropiat de ei repede, dar uneori am vrut să fiu singur și a rămas la un hotel.

Am stat la București 2 săptămâni, iar apoi m-am dus la Horezu, în județul Vâlcea. Lângă Gara de Nord, am întâlnit-o pe Cristy, o fată de 14 de ani din Horezu, se plimba în jurul gării în așteptarea trenului spre casă. Ea a spus Horezu este frumos. Am întrebat-o dacă există oi în Horezu, dacă este sau nu munte, iar ea a răspuns: "Da". Mi-am imaginat scene din filmul de animație ”Heidi în Alpi”.

După o ședere de 2 săptămâni la București, nu am mai fost atât de interesat de ”revolutie”. Am fost acum interesat de România, nu de mișcarea politică în Europa de Est. O posibilă conexiune este nu legata de Japonia sau istoria ei, ci una a mea, o căutare interioara personală. Un lucru care m-a impresionat a fost faptul că românii erau atât de liberi, chiar și după 35 de ani de presiuni politice din comunism.

De atunci, m-am întors în România aproape în fiecare an, până în 2001. Cea mai mare parte a timpului petrecut în România, între 1990 și 2001, a fost la București și Horezu. Pe parcursul acestei perioade de timp, am călătorit între Japonia și România un total de 2 ani sau mai mult, în 10 vizite.

M-am întors în România, în sfârșitul lunii decembrie 1990, pentru că prietenul meu de la Horezu mi-a propus să ne petrecem Crăciunul acolo, să văd tradițiile lor și să încerc mâncarea românească de Crăciun.

În București, într-un bar mi-a fost furat aparatul de fotografiat Nikon FE. Prietenul meu Valentin mi-a împrumutat un aparat de fotografiat telemetru sovietic (Fed 2), pentru că nu am avut o experiență cu acest tip de aparat de fotografiat multe dintre imaginile luate nu sunt focalizate și au calitate proastă,. O săptămână mai târziu, Valentin a primit un telefon de la secția de poliție, spunând că mi-au găsit aparatul foto, așa că am fost foarte fericit că am putut folosi din nou Nikon-ul meu. Frigul din România (iarna este mai rece în România decât în Japonia) m-a făcut să-mi schimb stilul de fotografiere, fotografiile mele redau o atmosferă diferită, greu de descris în acel moment.Când m-am întors în Japonia am făcut un portofoliu tipărit și o expoziție la Shinjuku Tokyo, în 1996. Câteva fotografii au fost publicate în reviste foto, dar niciodată fotografii din excursia din 1990.

În prezent, țin legătura cu prietenii mei din România, prin Facebook sau Skype. De fapt, în toamna 2016, Valentin Diaconu m-a vizitat la Tokyo timp de 3 săptămâni.

Norihiro Haruta

Norihiro Haruta (www.facebook.com/norihiro.haruta), born in Japan in 1968, came in Romania in 1990 seeking the footprints of the Eastern Europe revolution. As a young student he describes Romania and Bucharest as being exotic, a place like he’s never seen before. What’s more interesting is that even though his memoirs were written after 27 years, he managed to keep alive his student naivety and to pass over emotions experienced in a world totally different from his home world.

During his stay, the young Norihiro Haruta made some short-term Romanian friends till he met, in the winter of 1990, Valentin Diaconu, a high school student that remained his friend for life. Valentin Diaconu says: "I met Nori in Horezu during the Christmas holidays. After some time, he came to visit me in Bucharest, lodging him in Ozana, a neighborhood where I used to live with my parents. We became friends and thanks to him I started to be fascinated by photography. In 1996, after I completed my economic studies, I chose to become a freelance photographer. In the fall of 2016, I visited Nori in Tokyo and so I fulfilled my promise made in the early of ‘90.”

The image archive we received from Norihiro Haruta showing Bucharest in the ‘90 includes over 500 photos. I'm glad and grateful that Valentin Diaconu have persuaded him to send us so many photos.

Mihai Petre further helped us and transformed this archive in a very precious testimonial by identifying the locations where the photos were made 27 years ago. Thank you Mihai, you are a true Bucharest lover and connoisseur. I also thanks to Sabin Prodan who assisted us in understanding the message of Norihiro Haruta.

Returning to the images sent by Norihiro Haruta, I find it almost impossible to believe that they reflect Bucharest. These images show a Bucharest that in 1990 was even uglier than it was during Ceausescu’s time. It is said that time heals and makes you forget things. That’s my case, because after 27 years I find myself wondering how I could have forgotten the hideous side of those years. 1990 was the first year after the Revolution when the country was ruled by what we call the “communists in the second line”. We had 3 mineriads, one of which had left us with scars for many years in 13th of June 1990. The National Salvation Front - FSN (a political organization that was the governing body of Romania in the first weeks after the Romanian Revolution in 1989) was the winner of the elections, its leader being Ion Iliescu, a former notable communist. Silviu Brucan said we needed 20 years to wake up; now, looking back I think he was an optimist.

1990 Bucureștiul mai urât decât pe vremea lui Ceaușescu

During those times, Bucharest was awful: queuing for food, shabby and ugly dressed people, crowded buses, shell game players and bagmen... an apocalyptic, degraded and hopeless Bucharest, the result of the first year of NSF government.

Nori, your photos, whether we like them or not, have a great value. They remind us a piece of the Romania history and help us understanding those times. Through your lens and eyes you have captured our honest reality and surprised our town in its true colors. For all of these I thank you so much!

I hope these photography will reach and be digested by the younger generations who were lucky not to live in Romania during Communism.

Andrei Bîrsan, president of Bucureștiul meu drag Association

Who was Norihiro Haruta in 1990? Where did you live, what were you doing, and how old were you when you came in Romania?

Nori: In the autumn of 1989, I was travelling to China, in the prohibition area of Tibet. I was trying to find the way, not ordinal route with permission, but the South route from Yunnan province to Tibet Autonomous Region in China without permission. On the ordinal route, police and security guards were waiting at the borders. Finally, someone informed and I got caught, in a small town somewhere in the mountains, in Yunnan province, where even foreigners could not get in.

Nori: In the autumn of 1989, I was travelling to China, in the prohibition area of Tibet. I was trying to find the way, not ordinal route with permission, but the South route from Yunnan province to Tibet Autonomous Region in China without permission. On the ordinal route, police and security guards were waiting at the borders. Finally, someone informed and I got caught, in a small town somewhere in the mountains, in Yunnan province, where even foreigners could not get in.

During the night, the security police got in my guest house room and took away to the military place, where they investigated my back ground, to see if I was a dangerous guy or not . They found my memo where I wrote the plan in Japanese. They, the Chinese, can understand the Japanese letters because Japanese is similar to Chinese. Japanese is basically used in Chinese letters from 6th century. Two days after, they admitted I was good man and they forced me to get out of that area by pushing me to the public bus, saying `Go home Japanese boy `.

I returned to Hong Kong. Hong Kong was my base, safe and intimate place. I could had a cheaper flight to go back to college, in Tokyo, where I was studying Sociology.

As a photographer, I just started to know about photo journalism, like MAGNUM and Life magazine, but I actually didn’t know anything about photography.

I bought a Nikon, Fuji Presto 400, and a Kodak tri-x400 and just tried taking pictures. I know that’s all I wanted to do. Not studying photography, not knowing photography, just getting me inside of somewhere which I feel dramatic, the darkness inside of my mind, and taking pictures, physically, outside of me, on the world stage.

In Hong Kong I arrived in November 1989. Then I saw the news about the Fall of the Berlin Wall. Newspapers and magazines front pages were writing about the Fall of the Wall, with historical exciting photos. I was wondering if I could go directly to Berlin from Hong Kong, without going back to Tokyo. I was excited to think about it. I chose to go home.

Since I came back to Tokyo, the place name called Eastern Europe enlivened the Japanese media. Eastern Europe was making my life as good in Japan, which was quite a fast time for my generation. Probably older Japanese knew East and Communism due to their exciting 1968-1970s youth days in Japan, but I was born in 1968. I lived during the Cold War.

After the 1970s, Japan just started to accelerate its economic development. Industries, technology, GDP, convenient electricity, investments, and material consume and so on. In the world it was the Cold War.

In Japan, I was living on the West side. I was holding a TV box, gathering information, news programs every night in my tiny room, reporting the East Revolution process, what happened or not, but I also recognized that Japanese journalism was so narrow and without having international eyes you won’t be able to understand what is true, real or not. At that time, NHK was ok, in one way at least, for international review, basically comparing it to the other media.

Between West and East – Asia and Japan.

From April 1990, I took one year off from my college, and I planned to visit Eastern Europe. I tried to see what is Europe, The European Modern Civilization, and revolution in Eastern Europe.

I had a Nikon FE, F, 24mm, 50mm, 85mm, 135mm, and 100 Fuji Presto 400 Presto films. I am not sure about these things. In fact, I don’t remember what camera I had; it’s a long time ago…

I went to Berlin, at last, to see the Reunification moment between East and West Germany. It’s June to August 1990.

Why Romania, how did you get the idea to visit, how did you hear about us, what did you know about us, Bucharest people, about the revolution? Have you been in Romania before? What was the period of time when you were visiting?

Between June and August 1990, I was living in a private youth hostel in Berlin, amongst many travelers and backpackers who were living, traveling, talking, drinking, and walking around Berlin and around Eastern Europe. After The Cold War finished, people from West went to the other side, which was hidden in East side. They were stopping in Berlin, and then leave for Prague, Budapest, and Poland, but no one was going to Romania. Me neither, even I didn’t know what happened in Romania after Ceausescu died.

One night, in the youth hostel, travelers were sitting in the living room, chatting about European future, economy and politics etc. I didn’t understand English well, but it was ok.

On a TV live show there were news briefings about Romania. I liked it and I was interested, but the other traveler were not.

Those travelers said the historical revolution moment has finished in Czech, Poland and Hungary, but news showed that Romania was still in the process of a revolution. Romanian police was hitting students. This scene was taking place in Bucharest. I felt that this is the moment for the revolution.

I asked what the news said because I didn’t understand the news in German, but they didn’t understand it either.

After a moment, I decided to go to Romania. At least if I had visited to Romania, I could feel the revolution, the hint of `Civilization` which Japan never had, and it’s still in distress between Japan-self and `Civilization`.

Then I took the train from Berlin to Bucharest.

Please tell us how your trip to Bucharest was. Some thoughts, happenings, the people you met? What did you do here, where did you live?

During the night, the train finally stopped at the border between Hungary and Romania. At midnight, the Border Security got into the train and checked the luggage and passports. They were strangers who smelled like alcohol and cheese. Actually, the train smelled like mass chaos for a person coming from Japan. My nose, body, food, blood, voice, was all different. Even the authority men. They checked and asked something.

At sunrise, a while after crossing the border, the train was in Romania. I looked through the window and I saw the golden field, beautiful plain, with wheat or cornfield.

Then the passengers in the train changed. The talking in the compartment was calm now. After this time on a long trip from berlin, them being quiet and gentle, made me tickle.

Next midnight the train arrived in Bucharest, at Gara de Nord. I found a Hotel near the train station at $20 per night.

I woke up late in the morning and the front desk woman told me about a nearby restaurant. I opened the door, went out, and then I saw for the first time Bucharest in the sun light. It’s the end of August; sun was great and the fine humidity was good too. I was standing in front of this city. That was the somewhere I had never seen. A dusty town in the sunshine, the tram running on the rough stone pavement, the bell ringing, horse cars passing, country of wherever. It was totally different from Berlin.

The people in Bucharest were friendly. They call me ‘Frate’ - brother. Sometimes I was staying at someone’s house, student, worker, friends of friends, you know. Some people were incredibly friendly to me, and I got close to them fast, but sometimes I wanted to be alone and stayed at a hotel. I was in Bucharest for 2 weeks, and then I went to Horezu, in Vâlcea County.

Near Gara de Nord, I met Cristy. A 14 years old girl, living in Horezu, she was walking around the train station. She was waiting for the train to take her back home. She said Horezu is beautiful. I asked her if there were sheep in Horezu, if it’s mountain or not, and she answered “Yes”. I imagined the animation `Heidi in the Alps`.

What made me change?

After a 2-week stay in Bucharest, I was not so interested in the `revolution` anymore. I was now interested in Romania, not the Eastern European political movement. A possible connection, would be the search for something to myself, not Japanese and or Japanese history, but something which has been my personal mental search. One thing which impressed me was that Romanians were so free even after the 35 years of political pressure from the communism.

Since then, I came back to Romania almost every year until 2001. Most of the time I spent in Romania between 1990 and 2001, I was in Bucharest and Horezu. During this period of time I travelled between Japan and Romania a total of 2 years or more, in 10 visits.

What did you do when you returned to Japan? Did you show somebody the photos? Did you printed them or exhibited them?

I printed and made a portfolio. I made one exhibition at Shinjuku Tokyo in 1996. Some photo magazines published a few, but never 1990’s trip photos.

Have you returned to Romania since then? What is your current relation to Romania? What is your occupation now?

Currently I made contact with my friends in Romania, by Facebook Messenger or Skype. Actually, this November 2016, the Romanian photographer Diaconu Valentin travelled to Tokyo for 3 weeks.

I have not been to Romania because of my economic depression, and maybe my age. I am in a bad situation which doesn’t allow me to visit Romania.